I’m glad not to be an art student these days. My illustration students are up against a social challenge I’m not sure I would have survived. When I was at Parsons in the late ‘90s, the internet was an experiment. By the time I graduated, I knew how to hand-code HTML and JavaScript, so I was a relatively early adopter, but there was no social media, and artists still dropped off portfolios at publications like the New York Times.

Ah, how times have changed. Take the pressure of graduating from a school whose tuition is now 51,400 dollars a year (plus NYC room and board! )—that’s a quarter-million dollars for a freelance-based occupation—the pressure on most of my students to try to keep their visas to stay in the United States, and add to that the belief that in order to have a successful career, these introverts have to become, on some level, social media influencers.

Then add the dynamics of what it takes to be an influencer. Histrionics and hot takes on world events (that most know ZERO about, but somehow still have an opinion on)—all wrapped up in a package of perfect looks in a curated environment or at least the front seat of a decent car, well-lit, no flaws—to become a perfect expert at 23 years old.

Call the Miss America Organization, stat!

Can you imagine this combination producing anything but anxiety, depression and identity issues among people whose prefrontal cortexes are not yet solidified, who are navigating their early 20s, maybe trying to find a partner and deciphering mixed messages about fertility at peak childbearing age—and from that, making work of any integrity??

This, my friends, is the death of art.

That is, should these young artists choose to follow that path. They have a choice, and it’d be good for them to make it now.

In my classes, I try to give my students a realistic and holistic picture of what it takes to have a career as an illustrator. No varnish; it’s brass tacks and hard numbers, with, yes, acknowledgments of the emotions and physical injuries inherent in this game; but we often talk about not letting emotions or whim or fads lead our decision-making, because we want long careers, not the average length before most artists burn out…which is ten years. I’ve been doing it for almost thirty.

The other thing I’ve been doing while being a working artist is paying fairly close attention to politics. I hate politics. I do everything in my power to de-politicize my worldview, my decision-making, my relationship to my body, my relationships. I hate politics, and yet I pay attention, because part of my job is writing historical novels and recognizing patterns. But don’t get it twisted: politics is also the death of art. A lot of artists like to style themselves as “activists” these days. And to be sure, art history is replete with political art, like this paradigm-shattering piece by Honoré Daumier:

That painting definitely upset the societal narrative of its time, but it was a time of less sophisticated avenues of communication when such art could disrupt. In our information-saturated world, does overtly political art still make an impact? I’m not so sure. We’re apt to scroll-and-forget within 20 seconds; I think that means artists should reconsider their pacing and positioning.

And in this environment, artists who consider themselves to be primarily working in the political space run the risk of becoming siloed and un-nuanced. How many times can an artist rage-draw derogatory images of Trump before they lose their ability to understand things like policy or foreign relations or the concerns of the working class? These things take time and deep consideration, not just emotional immediacy.

Not to mention that illustration, which used to be a working-class profession until not too long ago, is now such an expensive endeavor that it almost guarantees these young artists are entering their careers already siloed.

I believe that these artists run the risk of becoming like Stalin’s propagandists, thinking they’re being creative while really trying to please the cultural censors or gatekeepers. For example, legend has it that this poster got the illustrator, um, disappeared; something about not liking how the dictator’s hands were drawn:

At this point, with a few historical novels under my belt, and a good, salty outer-boroughs upbringing grounded in ‘80s and ‘90s anti-censorship, I’ve developed a pretty good nose for propaganda. The lack of solid reality in my family of origin also gave me a good BS-meter: I can quickly sense when I’m being lied to or manipulated. I’ve learned, over time, how to be a little…ugh… “nicer”, a little more diplomatic—this is the “Vesper” many of you know or have met—but trust me, as I get older, the edge gets sharper and slips out at inconvenient times.

I make no apologies.

So when it comes to the political sphere in the last ten years, I’ve had to put all of that instinctual reflex in the driver’s seat and put a brick on the accelerator. It’s paid off. I’m more of an Independent than I ever was when I first registered to vote all those years ago. My primary value as an artist is that I will not be bought. I will not be forced to make this or that statement unless it is truly coming from my own belief. I’ll even stay silent on things I do believe if I suspect my words will be twisted against me or used to infer things I never said.

I’ve fought too hard for my work for too long to let it, or my sense of self, be co-opted by political factors. I want the truth straight-no-chaser, and what I will deliver to you as the reader/viewer of the work is the most honest assessment of the world as I see it (which I fully acknowledge that you may not share, and that’s the point, i’int it.1). My work may include a presentation of political ideas you don’t like, or philosophical ideas you don’t agree with, or the life of someone in whose shoes you’ve never walked. I want to open worlds to you, not close them in. That’s what art does.

The other day, I was speaking with an Israeli friend about the election here, and we agreed on the need to keep ourselves distant from politics. We are both artists, and only over time have we discovered that our understanding of politics is more or less aligned and equally nuanced.

She quoted this passage from The Marginalian:

“A century of upheavals ago, suspended between two World Wars, Hermann Hesse (July 2, 1877–August 9, 1962) considered the strange power and possibility of such societal phase transitions in his novel Steppenwolf (public library). He writes:

Every age, every culture, every custom and tradition has its own character, its own weakness and its own strength, its beauties and ugliness; accepts certain sufferings as matters of course, puts up patiently with certain evils. Human life is reduced to real suffering, to hell, only when two ages, two cultures and religions overlap. A man of the Classical Age who had to live in medieval times would suffocate miserably just as a savage does in the midst of our civilisation. Now there are times when a whole generation is caught in this way between two ages, two modes of life, with the consequence that it loses all power to understand itself and has no standard, no security, no simple acquiescence.

“We too are living now through such a world, caught again between two ages, confused and conflicted, suffocating and suffering. But we have a powerful instrument for self-understanding, for cutting through the confusion to draw from these civilizational phase transitions new and stronger structures of possibility: the creative spirit.

“Hesse observes that artists feel these painful instabilities more deeply than the rest of society and more restlessly, and out of that restlessness they make the lifelines that save us, the lifelines we call art. A century before Toni Morrison, living through another upheaval, insisted that “this is precisely the time when artists go to work,” Hesse insists that artists nourish the goodness of the human spirit “with such strength and indescribable beauty” that it is “flung so high and dazzlingly over the wide sea of suffering, that the light of it, spreading its radiance, touches others too with its enchantment.”

“This is exactly why artists must never be forced into ideology,” I said to my friend. We have to keep a certain distance to be able to see clearly, precisely bc our work is so vital.”

“Yes, exactly,” she responded. “And it’s often why we don’t fit either grouping…to witness so much…see more than most.”

And that’s it, right there. I’m no influencer, or pundit, or activist, or politico. I’m an artist. My job is to “see more than most”, to respond to it, and to report back what I’ve seen. And my deep conviction as an artist is that I demand my ideological independence. And anyone who claims, as numbers of shallow-minded numbskulls in my presence have over the years, to know “my politics”, is going to have to crawl over my cold, dead body covered in broken glass and live coals to know what “my politics” are, or to get a piece of my mind or my self that I don’t give them.

SO. The election.

I’m sorry to disappoint, but you’re not going to know who I voted for in this or any election. I promise you’d never guess, and I’ll never divulge that information again; I haven’t since, I don’t know, 2008? There are, more or less, about seven people in my entire life who know my choices, and it’s because they are the rare folks who get a vote in my life.

This is why we have a secret ballot in the United States. I like that. As much as I hate politics, I also don’t like totalitarian systems, or dictators, or coercion, certainly not of artists. But I’ll just remind us that even in those instances, the artists always come out on top, always exonerated, always celebrated for making good, honest work about the realities they live in, while the memories of the despots rot. There’s Milan Kundera. Vàclav Havel. Csezlaw Milosz.

Politics is the death of art.

No matter how you voted, I want to encourage you to fight for your own mind. Whether you’re a young artist navigating a scary new adult world, where your pattern recognition is still being tuned; or you’re in middle age trying to hold on to your youthful idealism while infusing it with the wisdom you’ve learned from some hard knocks; or a seasoned elder realizing how little actually changes in this dark-yet-lovely world and that the real point of life is loving a small group of people very well, I want to encourage you today to hold on to your mental independence.

Hold on to the right to your own mind, to think for yourself, to remember that you have agency in this world, and that neither the State nor the culture can read your mind, whether times are free or restricted, whether the culture is dominated by Left or Right, whether the State is Red or Blue. None of these things have any value to offer to the creative mind. These paradigms are useful only insofar as they are useful. Know what I mean?

The world, and your country, are full of people who want to love life just as much as you do. People are different. Complex. Interesting. Bigger on the inside than on the outside. Good stories are never one-sided, just like good nations are never one-partied.

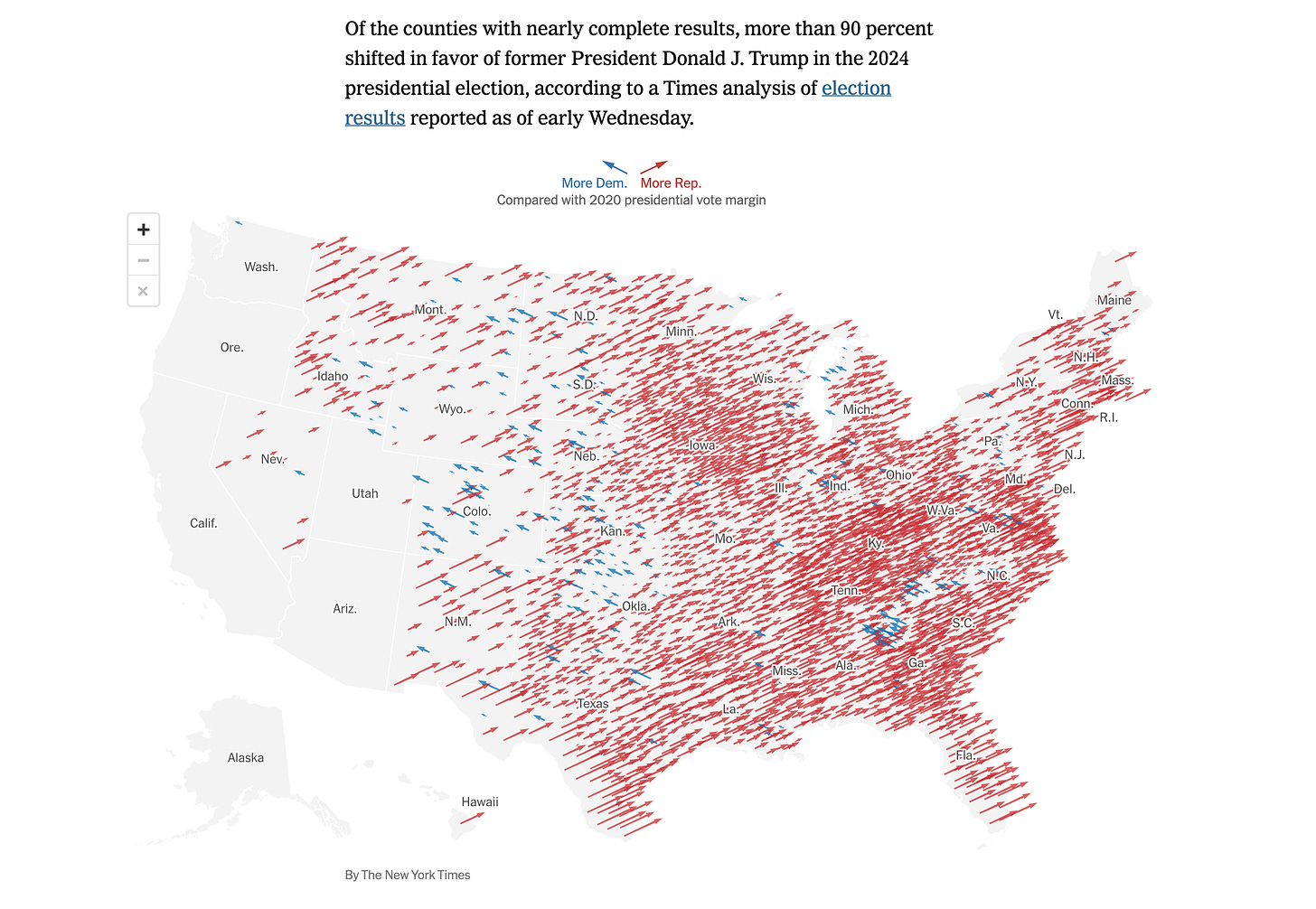

If this election showed us anything, it’s that we all made assumptions about our neighbors that weren’t true. Anyone still thinking of estranging their family members over their politics is going to be extremely lonely pretty soon. (Estranging your family over politics makes you one of the baddies, by the way. I’m dead serious.) Over half the country voted for the new president-elect. Are all of those people fascists? When New York and California each shifted right by thirteen points?

We can wring our hands over all of this, continue the hysterical rhetoric about waking up in a Handmaid’s Tale dystopia (oh my GOODNESS can we stop with that tired trope), or this gem:

An AI-generated, anti-Trump campaign ad that shows a post-Trump triumvirate dictatorship of Elon Musk, Peter Thiel and JD Vance, complete with Musk achieving immortality. It has to be seen to be believed. Sorry, but she didn’t seem like she was having a particularly good time at that party before Elon became immortal and Blew Up Earth. If that’s your idea of a beautiful life or a good party, I can’t help.

Don’t get me started on the right-under-the-surface racism of our vaunted “trusted” news anchors, seated on their thrones of privilege, blaming black men and Latinos for getting the Big T elected. And don’t get me started about the reckless comparisons to Hitler and Nazis and concentration camps. Just do not dare me on this subject.

To blame women, who make the majority of the financial decisions in this country, for “voting against their own interests“ or “internalized misogyny“ because they have policy differences on abortion—or better yet, didn’t consider it their driving issue—that even the president elect doesn’t share, is disgusting. Many, many women are pro-life, including the ones who do the unseen work of caring for women with unplanned pregnancies, buying diapers for their babies out of their own pockets, and volunteering at shelters and crisis homes. It’s not men driving this issue. It’s women.

I want to talk about this phrase: “voting against one’s own interests.” This concept actually comes from a Marxist term called “class consciousness.” The belief that Marxist/Communist theory is superlatively true—that the poor and working classes are only awaiting enlightenment, or “achieving class consciousness”, in order to throw off their fetters, overthrow their enslavers, and engage in the “revolution”—is intensely religious, magical-thinking woo.

I interviewed an avowed Marxist academic for my novel, Berliners (which you should definitely read, and buy for everyone this Christmas). He was committed to the Theory, but not someone who could really figure out his own life. I was glad we weren’t on a video call for what he actually said to me, out loud, because my jaw hit the floor:

“They need people like us to tell them what they need, because they don’t know what they need.”

This was the perfect illustration of “class conscious” thinking. It reduces people to their economic class, or their Enlightenment-pseudo-scientific-racialist demographic — black, Latino, woman — and says that all widgets within these particular boxes must necessarily have the same interests. It says that the people within those categories, if they do not act according to the theorists’ version of reality, are therefore betraying the revolution.

For all that we’ve heard over the past ten years about systemic racism, does anyone fail to see how truly classist, racist and misogynist this is?

So the next time you hear someone use that phrase— “why are they voting against their own interests”— raise your hand and say, “that’s Marxist class consciousness, a Theory to which I do not ascribe and which would probably scandalize the people you’re talking about.”

I actually do not believe that people vote “against their own interests.” A wise woman once said to me something so simple, yet so profound: “We have what we want.” I agree with that completely. We may self-sabotage, but we always eventually have what we want. And for a majority of the country last week, that was not the message of the Democrat Party’s interests; it was the Republican ticket, all the way down-ballot.

That is democracy in action: the right to change your mind and vote for your own interests.

It would be one thing for Trump/Vance and the Republicans in general to have won by a slim margin and split the electoral/popular vote. But what happened on Tuesday was an overwhelming repudiation of the “let us tell you what your best interests are“ message. You can call this a “shift to the right”, but I do not believe that is what is going on here. I believe this is a reset to center from both sides.

If we don’t recognize this, whatever “side” (ho-hum") we’re on, we will miss a huge opportunity to right the ship. Or as my friend Dehavilland likes to say, “Left wing, right wing—the whole bird is sick.” Instead of hating our neighbors or making broad, sweeping generalizations about them based on class, race, gender or party, we could work to truly know each other again. If your team didn’t win this particular game, it doesn’t mean you don’t shake hands afterward. You can still invite them to your birthday party even if they go to a different school.

Or we can continue calling each other Hitlerian fascists (while knowing nothing about either term). Our choice, I guess.

As citizens, we have the right to demand better leaders for whom to vote, and demand better of the leaders we have. We have every right to contact our representatives with our concerns, sign a petition, even protest (those wanting to do away with the First Amendment might want to read the whole thing 2—better yet, the whole Constitution). These are elements of a healthy democracy (or constitutional republic, which is the actual system we live in, or did, before it became a corporate oligarchic empire).

But as artists, we need to demand the right to think, speak, act and create for ourselves, and to make the work that comes from our own processing of how we see the world and our own times. Complete honesty, with ourselves first. Detoxifying ourselves of political suasion. Humanizing the work instead of being slowly inched toward misanthropy.

The reason I am not crying tears of either joy or despair over the election results is that I don’t live by election results. The game is going to continue to be played regardless of who wins the election. Policy decisions will be made that we agree or disagree with. Politicians will say stupid things. Both the American “homeland” and the American “empire” (to put it in the very helpful paradigm put forward by Mike Benz), will keep rolling along with their disparate intrests.

When it comes to politics, I aim to live according to Psalm 146: “do not put your trust in princes or sons of men.” Nor in chariots or horses either. It’s possible to live life with a different infrastructure that ensures you don’t resort to cutting off all your hair if your chosen candidate loses a damn election, or drunkenly gloating if yours won. Meaning is to be found not in awful, low-resolution political results, but in serving other people; in being part of a truly diverse community; orienting yourself upwards instead of laterally; having a family and then doing the hard work of maintaining it and nurturing it. Those are human choices, not political ones. And it’s possible to even make that kind of life into a work of art.

I hope that the next four years will be characterized by everyone chilling the F out. I hope the rage fatigue sets in and we learn how to throw good parties again. I hope we learn to see our neighbors through our actual, physical, human eyes instead of TikTok turkey filters or whatever square we’re supposed to post next. I hope we learn how to fall in love again, which is, incidentally, what my next novel is about. I hope we make stupid rom-coms and nerdy space-exploration flicks and get excited about the velcro sounds on our Trapper Keepers. I hope we learn how to fold notes into neat triangles and pass them to the boys we like with heart-bedazzled checklists of “will you go out with me yes/no”. Because I’m ready to remember what it meant to get legit chills or feel the hair stand up on my arms or feel my heart drop with romance.

That is real life. That is what art is made of. That is how culture is resurrected—by reclaiming our physical humanity and real, in-person, un-social-distanced relationships. Anything less than that, I frankly don’t have enough years left to indulge.

Over these next four years, instead of rage or schadenfreude, build a life you can be proud of, love your neighbor, and even look for ways to love your enemies. That’ll do.

Years ago I was on an author panel at which a lovely young man asked a question about one of my protagonists, and said that he wouldn’t have made the same decisions as her. He was apologetic for this. I answered, “Why in the world would you apologize for disagreeing with someone? She’s not you, and you’re not her. Where did we get this idea that we have to agree with the protagonist in a work of fiction, let alone in real life?” I applauded him for his individual thinking and encouraged him to keep at it.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Thank you so much for this insightful post, Vesper.

Beautiful! I want to read this to my art students🥰